Black History Art: Malick Sidibé

Kali Abdullah

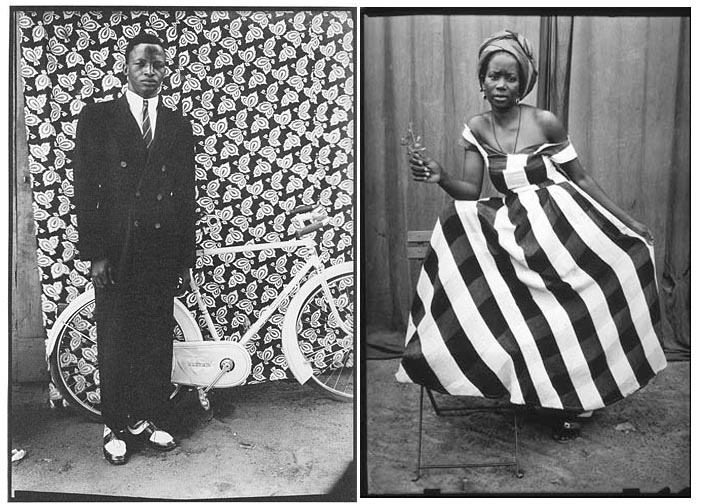

Malick Sidibé (born in 1936) is a Malian photographer noted for his black-and-white images chronicling the exuberant lives and pop culture, often of youth during the 1960s and 70s in Bamako. His work documents a transitional moment as Mali gained its independence and transformed from a French colony steeped in tradition to a more modern independent country looking toward the West. He captured candid images in the streets, nightclubs, and sporting events and ran a formal portrait studio.

Malick Sidibé is a generation behind Seydou Keïta and I’d like to think that he was influenced by Keïta’s photography. Similar to Keïta, Sidibé was a studio photographer known for his black-and-white portraits, but what set him apart is the sense of youthful pride and fun captured in the photographs. He enjoyed using the studio as a way to pretend and create new lives for his subjects. Also people enjoyed coming to his studio because unlike the others he had electricity, which was a luxury at the time. When talking about his studio portraits he states in an interview:

“As a rule, when I was working in the studio, I did a lot of the positioning. As I have a background in drawing, I was able to set up certain positions in my portraits. I didn’t want my subjects to look like mummies. I would give them positions that brought something alive in them. When you look at my photos, you are seeing a photo that seems to move before your eyes. Those are the sort of poses I gave them. Not poses that were inert or lifeless. No. People who have life need to be positioned that way. It was quite different at my studio. It was like a place of make-believe. People would pretend to be riding motorbikes, racing against each other. It was not like that at the other studios. That’s why my studio was so popular, already by 1964, 1965. The studio was a lot more laid back.”

I was first introduced to Malick Sidibé in 1997 when Janet Jackson put out the “Got ‘til It’s Gone” song featuring Q-Tip and Joni Mitchell. The music video, directed by Mark Romanek used African photography as a motif, creating what he called a "pre-Apartheid celebration based on that African photography." The video wanders a massive house party and includes scenes inspired by the work of photographer Malick Sidibé. After falling in love with the video and being an aspiring photographer at the time I dove deep into finding out what Sidibé was all about. I love how Sidibé captured the essence of that time period and the sixties and seventies fashion. It gave me a whole new perception of African culture, which before then I thought was very traditional and tribal.

Joni Mitchell, Janet Jackson & Mark Romanek discuss the Music Video "Got 'Till It's Gone" Includes music video by Janet Jackson w/Q-Tip and Joni Mitchell - "Got 'Til It's Gone" (Def Radio Mix). (C) Virgin Records. Directed by Mark Romanek. From the album "The Velvet Rope"

I also learned that Malick Sidibé was like the original club photographer in Bamako (days before social media). In an interview with lensculture.com he states:

“At night, from midnight to 4 am or 6 am, I went from one party to another. I could go to four different parties. If there were only two, it was like having a rest. But if there were four, you couldn't miss any. If you were given four invitations, you had to go. You couldn't miss them. I'd leave one place, I'd take 36 shots here, 36 shots there, and then 36 somewhere else, until the morning. Sometimes I would come back to parties where there had been a lot of people. Afterwards I had to develop the photos and print them out. Sometimes, right up to 6 in the morning, I would be at the enlarger. For the 6 x 6 films there was a contact printer, but the 24 x 36 had to be enlarged. You could work in the morning, but, by Tuesday, the photos had to be ready for display. The proofs were pinned up outside my studio. Lots of people would come and point themselves out. ‘Look at me there! I danced with so-and-so! Can you see me there?’ Even if they didn't buy the photo, they would show it to their friends. That was enough for them. They had danced with a certain girl, and that was enough. I wasn't happy, though. I wanted them to buy these photos!”

The true hustle of a photographer hahah.

Sidibé’s work has been exhibited extensively. His photos are in numerous public and private collections all over the world and he’s received several honors and awards. He has become a true inspiration in portrait photography for me especially in men's fashion and style.

In a 2010 interview with John Henley in The Guardian Sidibé explained, “To be a good photographer you need to have a talent to observe, and to know what you want. You have to choose the shapes and the movements that please you, that look beautiful. Equally, you need to be friendly, sympathetic. It's very important to be able to put people at their ease. It's a world, someone's face. When I capture it, I see the future of the world. I believe with my heart and soul in the power of the image, but you also have to be sociable. I'm lucky. It's in my nature."

Malick Sidibé presently resides in Mali.